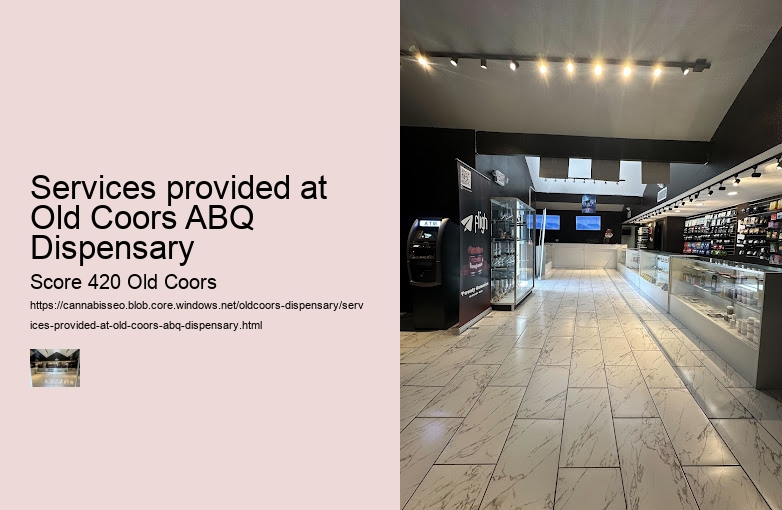

Edibles and infused products are a popular choice for many customers at Old Coors ABQ Dispensary. These items offer a convenient and discreet way to consume cannabis, whether you're looking for a tasty treat or a quick dose of relief.

Our selection of edibles includes a variety of options, from gummies and chocolates to cookies and brownies. Each product is carefully crafted with high-quality ingredients and precise dosing to ensure a consistent experience every time.

In addition to traditional edibles, we also offer infused products such as beverages, tinctures, and capsules. These products provide an alternative method of consumption for those who prefer not to smoke or vape.

Whether you're looking for a delicious snack or a convenient way to incorporate cannabis into your wellness routine, our edibles and infused products have something for everyone. Stop by Old Coors ABQ Dispensary today to explore our selection and find the perfect option for your needs.

Topical products are a fantastic addition to the array of services provided at Old Coors ABQ Dispensary. These products offer a unique and convenient way for customers to experience the benefits of cannabis in a discreet and effective manner.

Whether you're looking for relief from pain, inflammation, or simply want to pamper your skin with luxurious CBD-infused lotions and balms, our selection of topical products has something for everyone. Our knowledgeable staff can help guide you towards the best product for your needs and preferences.

From soothing muscle creams to rejuvenating skincare serums, our topicals are carefully curated to provide maximum benefits without any psychoactive effects. You can trust that each product has been rigorously tested for quality and safety, ensuring a premium experience every time.

So why not treat yourself to the wonderful world of topical cannabis products at Old Coors ABQ Dispensary? Your body will thank you, and your mind will be at ease knowing you're getting high-quality products from a trusted source. Come visit us today and discover the transformative power of topicals!

At Old Coors ABQ Dispensary, we offer a wide range of merchandise and accessories to enhance your cannabis experience. From stylish apparel to handy smoking tools, we've got everything you need to make your visit truly special.

Our merchandise selection includes t-shirts, hats, and other clothing items featuring our logo and unique designs that showcase your love for our dispensary. Whether you're looking for a comfortable outfit to wear while relaxing at home or a statement piece to show off at your next social gathering, we have something for everyone.

In addition to clothing, we also carry a variety of accessories to help you enjoy your cannabis products to the fullest. From rolling papers and filters to pipes and vaporizers, we have everything you need to elevate your smoking experience. Our knowledgeable staff is always on hand to help you find the perfect accessory for your needs and preferences.

So whether you're looking to stock up on some stylish merch or upgrade your smoking setup, be sure to stop by Old Coors ABQ Dispensary and check out our fantastic selection of merchandise and accessories. We can't wait to help you find the perfect items to enhance your cannabis journey!

At Old Coors ABQ Dispensary, we believe in rewarding our loyal customers for their continued support. That's why we offer a fantastic Loyalty Program that allows you to earn points every time you make a purchase. These points can then be redeemed for special discounts on future orders, making it even more affordable to enjoy our top-quality services.

In addition to our Loyalty Program, we also regularly offer Special Discounts on select products and services. Whether you're looking for a great deal on your favorite strains or want to try something new at a discounted price, our specials are sure to have something that catches your eye.

We understand the importance of providing top-notch service and products to our customers, and we believe that offering loyalty rewards and special discounts is just one way we can show our appreciation. So come visit us at Old Coors ABQ Dispensary and see how our exceptional service and unbeatable deals can enhance your cannabis experience.

Coordinates: 35°5′4″N 106°39′1″W / 35.08444°N 106.65028°WCountryUnited StatesStateNew MexicoCountyBernalilloMetropolitan areaAlbuquerque metropolitan areaFounded1706 (as Alburquerque)Incorporated1891 (as Albuquerque)Founded byFrancisco Cuervo y ValdésNamed afterFrancisco Fernández de la Cueva, 10th Duke of AlburquerqueGovernment

• TypeMayor–council government • MayorTim Keller (D) • City Council

• U.S. HouseMelanie Stansbury (D)

Gabe Vasquez (D)Area

194.93 sq mi (489.39 km2) • Land188.27 sq mi (486.03 km2) • Water1.62 sq mi (4.35 km2)Elevation

5,312 ft (1,619 m)Population

564,559 • Rank86th in North America

32nd in the United States

1st in New Mexico • Density3,014.68/sq mi (1,163.97/km2) • Urban

769,837 (US: 59th) • Urban density2,926.3/sq mi (1,129.9/km2) • Metro

1,162,523Demonym(s)Albuquerquean (uncommon), Burqueño, BurqueñaGDP

• Metro$59.383 billion (2023)Time zoneUTC−7 (MST) • Summer (DST)UTC−6 (MDT)ZIP Codes

Area codes505FIPS code35-02000GNIS feature ID2409678[2]Websitewww

Albuquerque (/ˈælbÉ™kÉœËrki/ ⓘ AL-bÉ™-kurk-ee; Spanish: [alβuˈkeɾke] ⓘ),[a] also known as ABQ, Burque, the Duke City, and in the past 'the Q', is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico,[6] and the county seat of Bernalillo County. Founded in 1706 as La Villa de Alburquerque by Santa Fe de Nuevo México governor Francisco Cuervo y Valdés, and named in honor of Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, 10th Duke of Alburquerque and Viceroy of New Spain, it was an outpost on El Camino Real linking Mexico City to the northernmost territories of New Spain.

Located in the Albuquerque Basin, the city is flanked by the Sandia Mountains to the east and the West Mesa to the west, with the Rio Grande and bosque flowing north-to-south through the middle of the city.[7] According to the 2020 census, Albuquerque had 564,559 residents,[8] making it the 32nd-most populous city in the United States and the fourth-largest in the Southwest. The Albuquerque metropolitan area had 955,000 residents in 2023, and forms part of the Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Los Alamos combined statistical area, which had a population of 1,162,523.[9]

Albuquerque is a hub for technology, fine arts, and media companies.[10][11] It is home to several historic landmarks,[12] the University of New Mexico, the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, the Gathering of Nations, the New Mexico State Fair, and a diverse restaurant scene, which features both New Mexican and global cuisine.[13]

Petroglyphs carved into basalt in the western part of the city bear testimony to a Native American presence in the area dating back many centuries.[14] These are preserved in the Petroglyph National Monument.

The Tanoan and Keresan peoples had lived along the Rio Grande for centuries before European colonists arrived in the area that developed as Albuquerque. By the 1500s, there were around 20 Tiwa pueblos along a 60-mile (97 km) stretch of river from present-day Algodones to the Rio Puerco confluence south of Belen. Of these, 12 or 13 were densely clustered near present-day Bernalillo, and the remainder were spread out to the south.[15]

Two Tiwa pueblos lie on the outskirts of present-day Albuquerque. Both have been continuously inhabited for many centuries: Sandia Pueblo was founded in the 14th century,[16] and Pueblo of Isleta is documented in written records since the early 17th century. It was then chosen as the site of the San Agustín de la Isleta Mission, a Catholic mission.

The historic Navajo, Apache, and Comanche peoples were likely to have set camps in the Albuquerque area, as there is evidence of trade and cultural exchange among the different Native American groups going back centuries before European arrival.[17]

Albuquerque was founded in 1706 as an outpost as La Villa de Alburquerque by Francisco Cuervo y Valdés in the provincial kingdom of Santa Fe de Nuevo México.[18] The settlement was named after the original town of Viceroy Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, 10th duke of Alburquerque, who was from Alburquerque, Badajoz in southwest Spain.

Albuquerque developed primarily for farming and sheep herds. It was a strategically located trading and military outpost along the Camino Real. It served other Tiquex and Hispano towns settled in the area, such as Barelas, Corrales, Isleta Pueblo, Los Ranchos, and Sandia Pueblo.[19]

After gaining independence in 1821, Mexico established a military presence here. The town of Alburquerque was built in the traditional Spanish villa pattern: a central plaza surrounded by government buildings, homes, and a church. This central plaza area has been preserved and is open to the public as a cultural area and center of commerce. It is referred to as "Old Town Albuquerque" or simply "Old Town". Historically it was sometimes referred to as "La Placita" (Little Plaza in Spanish). On the north side of Old Town Plaza is San Felipe de Neri Church. Built in 1793, it is one of the oldest surviving buildings in the city.[20]

After the New Mexico Territory became a part of the United States in the mid-19th century, a federal garrison and quartermaster depot, the Post of Albuquerque, were established here, operating from 1846 to 1867. In Beyond the Mississippi (1867), Albert D. Richardson, traveling to California via coach, passed through Albuquerque in late October 1859—its population was 3,000 at the time—and described it as "one of the richest and pleasantest towns, with a Spanish cathedral and other buildings more than two hundred years old."[21]

During the Civil War, Albuquerque was occupied for a month in February 1862 by Confederate troops under General Henry Hopkins Sibley. He soon afterward advanced with his main body into northern New Mexico.[citation needed] During his retreat from Union troops into Texas, he made a stand on April 8, 1862, and fought the Battle of Albuquerque against a detachment of Union soldiers commanded by Colonel Edward R. S. Canby. This daylong engagement at long range led to few casualties. The residents of Albuquerque aided the Republican Union to rid the city of the occupying Confederate troops.[citation needed]

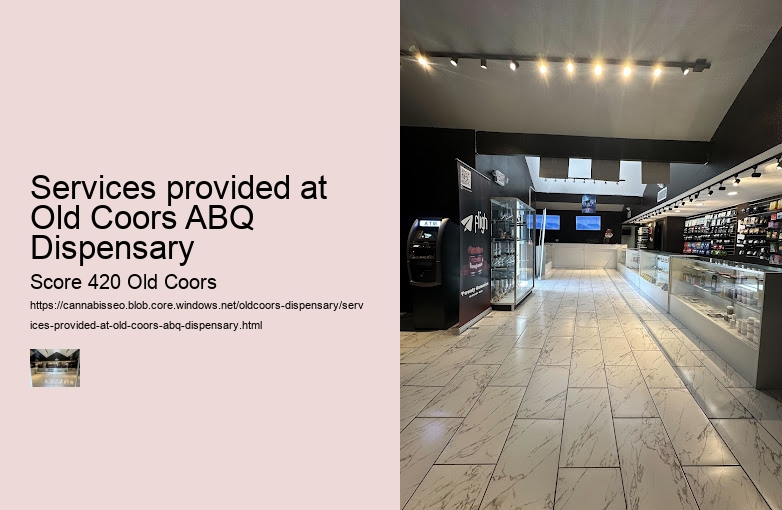

When the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad arrived in 1880, it bypassed the Plaza, locating the passenger depot and railyards about 2 miles (3 km) east in what quickly became known as New Albuquerque or New Town. The railway company built a hospital for its workers that was later used as a juvenile psychiatric facility. It has since been converted to a hotel.[22]

Many Anglo merchants, mountain men, and settlers slowly filtered into Albuquerque, creating a major mercantile commercial center in Downtown Albuquerque. From this commercial center on July 4, 1882, Park Van Tassel became the first to fly a balloon in Albuquerque with a landing at Old Town.[23] This was the first balloon flight in the New Mexico Territory.

Due to a rising rate of violent crime, gunman Milt Yarberry was appointed the town's first marshal that year. New Albuquerque was incorporated as a town in 1885, with Henry N. Jaffa its first mayor. It was incorporated as a city in 1891.[24]: 232–233

Old Town remained a separate community until the 1920s, when it was absorbed by Albuquerque. Old Albuquerque High School, the city's first public high school, was established in 1879. Congregation Albert, a Reform synagogue established in 1897, by Henry N. Jaffa, who was also the city's first mayor, is the oldest continuing Jewish organization in the city.[25]

By 1900, Albuquerque boasted a population of 8,000 and all the modern amenities, including an electric street railway connecting Old Town, New Town, and the recently established University of New Mexico campus on the East Mesa.[citation needed] In 1902, the Alvarado Hotel was built adjacent to the new passenger depot, and it remained a famous symbol of the city for decades.[26] Outdated, it was razed in 1970 and the site was converted to a parking lot.[27]

In 2002, the Alvarado Transportation Center was built on the site in a style resembling the old landmark. The large metro station functions as the downtown headquarters for the city's transit department. It also is an intermodal hub for local buses, Greyhound buses, Amtrak passenger trains, and the Rail Runner commuter rail line.[citation needed]

In the early days of transcontinental air service, Albuquerque was an important stop on many transcontinental air routes, earning it the nickname "Crossroads of the Southwest".[28]

During the early 20th century, New Mexico's dry climate attracted many tuberculosis patients to the city in search of a cure;[29] this was before penicillin was found to be effective. Several sanitaria were developed on the West Mesa for TB patients. Presbyterian Hospital and St. Joseph Hospital, two of the largest hospitals in the Southwest, had their beginnings during this period. Influential New Deal–era governor Clyde Tingley and famed Southwestern architect John Gaw Meem were among those who came to New Mexico seeking recovery from TB.[citation needed]

The first travelers on Route 66 appeared in Albuquerque in 1926. Soon dozens of motels, restaurants, and gift shops sprouted along the roadside. Route 66 originally ran through the city on a north–south alignment along Fourth Street. In 1937 it was realigned along Central Avenue, a more direct east–west route.[citation needed] The intersection of Fourth and Central downtown was the principal crossroads of the city for decades. The majority of the surviving structures from the Route 66 era are on Central, though there are also some on Fourth. Signs between Bernalillo and Los Lunas along the old route now have brown, historical highway markers denoting it as Pre-1937 Route 66.[citation needed]

The establishment of Kirtland Air Force Base in 1939, Sandia Base in the early 1940s, and Sandia National Laboratories in 1949, would make Albuquerque a key player of the Atomic Age. Meanwhile, the city continued to expand outward into the Northeast Heights, reaching a population of 201,189 by 1960 per the U.S. Census.[30]

By 1990, it was 384,736 and in 2007 it was 518,271. In June 2007, Albuquerque was listed as the sixth fastest-growing city in the United States.[31] In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Albuquerque's population as 34.5% Hispanic and 58.3% non-Hispanic white.[32]

On April 11, 1950, a USAF B-29 bomber carrying a nuclear weapon crashed into a mountain near Manzano Base.[33] On May 22, 1957, a B-36 accidentally dropped a Mark 17 nuclear bomb 4.5 miles from the control tower while landing at Kirtland Air Force Base. Only the conventional trigger detonated, as the bomb was unarmed. These incidents were not reported as they were classified as secret for decades.[34]

Following the end of World War II, population shifts as well as suburban development, urban sprawl and gentrification, Albuquerque's downtown entered a period of decline. Many historic buildings were razed in the 1960s and 1970s to make way for new plazas, high-rises, and parking lots as part of the city's urban renewal phase.[citation needed] As of 2010[update], only recently has Downtown Albuquerque come to regain much of its urban character,[citation needed] mainly through the construction of many new loft apartment buildings and the renovation of historic structures such as the KiMo Theater.

During the 21st century, Albuquerque's population has continued to grow rapidly. The population of the city proper was estimated at 564,559 in 2020,[35] 528,497 in 2009, and 448,607 in the 2000 census.[36] During 2005 and 2006, the city celebrated its tricentennial with a diverse program of cultural events.

The passage of the Planned Growth Strategy in 2002–2004 was the community's strongest effort to create a framework for a more balanced and sustainable approach to urban growth.[37]

Urban sprawl is limited on three sides—by the Sandia Pueblo to the north, the Isleta Pueblo and Kirtland Air Force Base to the south, and the Sandia Mountains to the east. Suburban growth continues at a strong pace to the west, beyond the Petroglyph National Monument, once thought to be a natural boundary to sprawl development.[38]

Because of less-costly land and lower taxes, much of the growth in the metropolitan area is taking place outside of the city of Albuquerque itself. In Rio Rancho to the northwest, the communities east of the mountains, and the incorporated parts of Valencia County, population growth rates approach twice that of Albuquerque. The primary cities in Valencia County are Los Lunas and Belen, both of which are home to growing industrial complexes and new residential subdivisions. The mountain towns of Tijeras, Edgewood, and Moriarty, while close enough to Albuquerque to be considered suburbs, have experienced much less growth compared to Rio Rancho, Bernalillo, Los Lunas, and Belen. Limited water supply and rugged terrain are the main limiting factors for development in these towns. The Mid Region Council of Governments (MRCOG), which includes constituents from throughout the Albuquerque area, was formed to ensure that these governments along the middle Rio Grande would be able to meet the needs of their rapidly rising populations. MRCOG's cornerstone project is currently the New Mexico Rail Runner Express.[citation needed]

Albuquerque is located in north-central New Mexico. To its east are the Sandia–Manzano Mountains. The Rio Grande flows north to south through its center, while the West Mesa and Petroglyph National Monument make up the western part of the city. Albuquerque has one of the highest elevations of any major city in the U.S., ranging from 4,900 feet (1,500 m) above sea level near the Rio Grande to over 6,700 feet (2,000 m) in the foothill areas of Sandia Heights and Glenwood Hills. The civic apex is found in an undeveloped area within the Albuquerque Open Space; there, the terrain rises to an elevation of approximately 6,880 feet (2,100 m), and the metropolitan area's highest point is Sandia Crest at an altitude of 10,678 feet (3,255 m).

According to the United States Census Bureau, Albuquerque has a total area of 189.5 square miles (490.9 km2), of which 187.7 square miles (486.2 km2) is land and 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2), or 0.96%, is water.[39]

Albuquerque lies within the fertile Rio Grande Valley with its Bosque forest, in the center of the Albuquerque Basin, flanked on the eastern side by the Sandia Mountains and to the west by the West Mesa.[40][41] Located in central New Mexico, the city also has noticeable influences from the adjacent Colorado Plateau semi-desert, New Mexico Mountains forested with juniper and pine, and Southwest plateaus and plains steppe ecoregions, depending on where one is located.

Albuquerque has one of the highest and most varied elevations of any major city in the United States, though the effects of this are greatly tempered by its southwesterly continental position.[citation needed] The elevation of the city ranges from 4,949 feet (1,508 m) above sea level near the Rio Grande[42] (in the Valley) to 6,165 feet (1,879 m) in the foothill areas of Sandia Heights.[43] At the Albuquerque International Sunport, the elevation is 5,355 feet (1,632 m) above sea level.[44]

The Rio Grande is classified, like the Nile, as an "exotic" river. The New Mexico portion of the Rio Grande lies within the Rio Grande Rift Valley, bordered by a system of faults, including those that lifted up the adjacent Sandia and Manzano Mountains, while lowering the area where the life-sustaining Rio Grande now flows.[citation needed]

Albuquerque lies in the Albuquerque Basin, a portion of the Rio Grande rift.[45] The Sandia Mountains are the predominant geographic feature visible in Albuquerque. Sandía is Spanish for "watermelon", and is popularly believed to be a reference to the brilliant pink and green coloration of the mountains at sunset. The pink is due to large exposures of granodiorite cliffs, and the green is due to large swaths of conifer forests. However, Robert Julyan notes in The Place Names of New Mexico, "the most likely explanation is the one believed by the Sandia Pueblo Indians: the Spaniards, when they encountered the Pueblo in 1540, called it Sandia, because they thought the squash growing there were watermelons, and the name Sandia soon was transferred to the mountains east of the pueblo."[46] He also notes that the Sandia Pueblo Indians call the mountain Bien Mur, "Big Mountain."[46]

Albuquerque lies at the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert transitioning into the Colorado Plateau. The Sandia Mountains represent the northern edge of the Arizona/New Mexico Mountains ecoregion.

The environments of Albuquerque include the Rio Grande bosque, (floodplain cottonwood forest), arid scrub, and mesas that turn into the Sandia foothills in the east. The Rio Grande's bosque has been significantly reduced and its natural flood cycle disrupted by dams built further upstream. A corridor of bosque surrounding the river within the city has been preserved as Rio Grande Valley State Park.

A few remaining natural arroyos provide riparian habitat within the city, though natural arroyos draining into the Rio Grande have largely been replaced with concrete channels. After a series of floods in the 1950s, passage of the "Arroyo Flood Control Act of 1963" provided for the construction of a series of concrete diversion channels.[47] The network of channels was built by the Army Corps of Engineers during the 1960s and early 1970s.[47]

Iconic urban wildlife includes the roadrunner, Gunnison's prairie dog, coyote, and New Mexico whiptail lizard. The bosque is a popular destination for wildlife viewing, with opportunities to see porcupines and sandhill cranes in the winter.[48] Cooper's hawks are common in city parks.[49]

Iconic vegetation includes the Rio Grande cottonwood in the bosque, and tree cholla, prickly pear, yucca, chamisa, and oneseed juniper in upland areas. The foothill open space at the eastern border also features Sonoran scrub oak and piñon pine. Desert willows are commonly planted throughout the city. Tumbleweeds are a common weed in disturbed areas, and are used by the city to make an annual holiday snowman.[50]

Albuquerque is geographically divided into four unequal quadrants that are officially part of mailing addresses, placed immediately after the street name. They are Northeast (NE), Northwest (NW), Southeast (SE), and Southwest (SW). Albuquerque's official quadrant system uses Central Ave for the north–south division and the railroad tracks for the east–west division. I-25 and I-40 are also sometimes used informally to divide the city into quadrants.

This quadrant has been experiencing a housing expansion since the late 1950s. It abuts the base of the Sandia Mountains and contains portions of the foothills neighborhoods, which are significantly higher in elevation than the rest of the city. Running from Central Ave and the Railrunner tracks to the Sandia Peak Aerial Tram, this is the largest quadrant both geographically and by population. Martineztown, the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, the Uptown area, which includes three shopping malls (Coronado Center, ABQ Uptown, and Winrock Town Center), Hoffmantown, Journal Center, and Cliff's Amusement Park are all in this quadrant.

Some of the most affluent neighborhoods in the city are here, including: High Desert, Tanoan, Sandia Heights, and North Albuquerque Acres. Parts of Sandia Heights and North Albuquerque Acres are outside the city limits proper. A few houses in the farthest reach of this quadrant lie in the Cibola National Forest, just over the line into Sandoval County.

This quadrant contains historic Old Town Albuquerque, which dates to the 18th century, as well as the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. The area has a mixture of commercial districts and low to high-income neighborhoods. Northwest Albuquerque includes the largest section of Downtown, Rio Grande Nature Center State Park and the Bosque ("woodlands"), Petroglyph National Monument, Double Eagle II Airport, the Paradise Hills neighborhood, Taylor Ranch, and Cottonwood Mall.

This quadrant also contains the North Valley settlement, outside the city limits, which has some expensive homes and small ranches along the Rio Grande. The city of Albuquerque engulfs the village of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque. A small portion of the rapidly developing area on the west side of the river south of the Petroglyphs, known as the "West Mesa" or "Westside", consisting primarily of traditional residential subdivisions, also extends into this quadrant. The city proper is bordered on the north by the North Valley, the village of Corrales, and the city of Rio Rancho.

Kirtland Air Force Base, Sandia National Laboratories, Sandia Science & Technology Park, the Max Q commercial district, Albuquerque International Sunport, American Society of Radiologic Technologists, Central New Mexico Community College, UNM South Campus, Presbyterian Hospital Duke City BMX, University Stadium, Rio Grande Credit Union Field at Isotopes Park, The Pit, Mesa del Sol, Isleta Amphitheater, Netflix Studios, Isleta Resort & Casino, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, New Mexico Veterans Memorial, and Talin Market are all located in the Southeast quadrant of Albuquerque.

The southern half of the International District lies along Central Avenue and Louisiana Blvd. Here, many immigrant communities have settled and thrive, having established numerous businesses.[citation needed] Albuquerque's Vietnamese American community is partly business-centered in this area, as well as the Eubank, Juan Tabo, and Central areas, and other parts of Albuquerque. There is also a Laotian American temple and a sizable community in parts of this area as well as around Uptown. There is also an African American community around Highland.[citation needed]

The Four Hills neighborhoods are located in and around the foothills on the outskirts of Southeast Albuquerque. The vast newer subdivision of Volterra lies west of the Four Hills area. Popular urban neighborhoods that can be found in Southeast Albuquerque include Nob Hill, Ridgecrest, Parkland Hills, Hyder Park, and University Heights.

Traditionally consisting of agricultural and rural areas and suburban neighborhoods, the Southwest quadrant comprises the south-end of Downtown Albuquerque, the Barelas neighborhood, the rapidly growing west side, and the community of South Valley, New Mexico, often called "The South Valley". The quadrant extends all the way to the Isleta Indian Reservation. Newer suburban subdivisions on the West Mesa near the southwestern city limits join homes of older construction, some dating as far back as the 1940s.[citation needed] This quadrant includes the old communities of Atrisco, Los Padillas, Huning Castle, Kinney, Westgate, Westside, Alamosa, Mountainview, and Pajarito. The Bosque ("woodlands"), the National Hispanic Cultural Center, the Rio Grande Zoo, and Tingley Beach are also here.

A new adopted development plan, the Santolina Master Plan, will extend development on the west side past 118th Street SW to the edge of the Rio Puerco Valley and house 100,000 by 2050.[51]

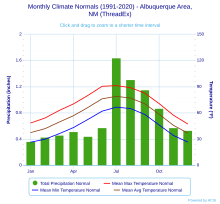

Albuquerque's climate is classified as a cold semi-arid climate (BSk) according to the Köppen climate classification system, while The Biota of North America Program[52] and the U.S. Geological Survey describe it as warm temperate semi-desert.[53][54]

| Climate data for Albuquerque (Albuquerque International Sunport), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1891–present[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

79 (26) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

98 (37) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

72 (22) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.9 (16.1) |

67.5 (19.7) |

76.8 (24.9) |

83.2 (28.4) |

91.2 (32.9) |

99.3 (37.4) |

99.4 (37.4) |

96.1 (35.6) |

91.7 (33.2) |

83.6 (28.7) |

71.1 (21.7) |

60.8 (16.0) |

100.8 (38.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 48.4 (9.1) |

54.1 (12.3) |

62.8 (17.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

79.9 (26.6) |

90.4 (32.4) |

91.2 (32.9) |

88.8 (31.6) |

82.5 (28.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

70.3 (21.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.4 (3.0) |

41.9 (5.5) |

49.5 (9.7) |

56.8 (13.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

76.1 (24.5) |

78.9 (26.1) |

76.9 (24.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

45.7 (7.6) |

36.9 (2.7) |

57.9 (14.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.4 (−3.1) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

36.2 (2.3) |

43.2 (6.2) |

52.4 (11.3) |

61.9 (16.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

58.1 (14.5) |

46.1 (7.8) |

34.1 (1.2) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

45.5 (7.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 15.4 (−9.2) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

39.6 (4.2) |

52.3 (11.3) |

60.6 (15.9) |

59.0 (15.0) |

47.4 (8.6) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

13.7 (−10.2) |

10.9 (−11.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −17 (−27) |

−10 (−23) |

6 (−14) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

46 (8) |

26 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

−7 (−22) |

−16 (−27) |

−17 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.36 (9.1) |

0.43 (11) |

0.46 (12) |

0.51 (13) |

0.44 (11) |

0.57 (14) |

1.64 (42) |

1.31 (33) |

1.15 (29) |

0.87 (22) |

0.57 (14) |

0.53 (13) |

8.84 (225) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.4 (3.6) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.9 (2.3) |

2.8 (7.1) |

7.9 (20) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 56.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 8.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56.3 | 49.8 | 39.7 | 32.5 | 31.1 | 29.8 | 41.9 | 47.1 | 47.4 | 45.3 | 49.9 | 56.8 | 44.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.0 (−7.8) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

19.2 (−7.1) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

35.4 (1.9) |

49.1 (9.5) |

50.4 (10.2) |

44.1 (6.7) |

32.5 (0.3) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 234.2 | 225.3 | 270.2 | 304.6 | 347.4 | 359.3 | 335.0 | 314.2 | 286.7 | 281.4 | 233.8 | 223.3 | 3,415.4 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 75 | 74 | 73 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 76 | 75 | 77 | 80 | 75 | 73 | 77 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[55][56][57] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for South Valley, New Mexico (elevation 4,955 ft (1,510.3 m), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1991–2022) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

101 (38) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

79 (26) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 64.2 (17.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

79.3 (26.3) |

84.1 (28.9) |

91.7 (33.2) |

99.9 (37.7) |

100.3 (37.9) |

97.2 (36.2) |

92.9 (33.8) |

84.5 (29.2) |

73.0 (22.8) |

63.5 (17.5) |

101.4 (38.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

57.1 (13.9) |

65.5 (18.6) |

72.4 (22.4) |

80.9 (27.2) |

90.9 (32.7) |

92.5 (33.6) |

90.1 (32.3) |

83.4 (28.6) |

72.2 (22.3) |

59.7 (15.4) |

49.9 (9.9) |

72.1 (22.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.7 (2.6) |

41.9 (5.5) |

49.3 (9.6) |

56.2 (13.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

73.9 (23.3) |

78.0 (25.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

68.6 (20.3) |

56.8 (13.8) |

44.6 (7.0) |

36.1 (2.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

33.1 (0.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

48.1 (8.9) |

56.8 (13.8) |

63.4 (17.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

53.9 (12.2) |

41.4 (5.2) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

41.6 (5.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.9 (−12.3) |

13.5 (−10.3) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

46.4 (8.0) |

56.1 (13.4) |

54.1 (12.3) |

42.3 (5.7) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

15.8 (−9.0) |

10.4 (−12.0) |

6.9 (−13.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

−5 (−21) |

6 (−14) |

22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

15 (−9) |

9 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.45 (11) |

0.47 (12) |

0.54 (14) |

0.59 (15) |

0.48 (12) |

0.57 (14) |

1.53 (39) |

1.52 (39) |

1.26 (32) |

1.02 (26) |

0.59 (15) |

0.65 (17) |

9.67 (246) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.4 (3.6) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.6 (1.5) |

2.3 (5.8) |

6.8 (17) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 56.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 4.9 |

| Source: NOAA[58][55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Albuquerque Foothills (elevation 6,120 ft (1,865.4 m), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1991–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

71 (22) |

81 (27) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

86 (30) |

75 (24) |

64 (18) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.2 (14.0) |

63.7 (17.6) |

73.9 (23.3) |

80.2 (26.8) |

88.8 (31.6) |

96.3 (35.7) |

96.6 (35.9) |

93.4 (34.1) |

88.7 (31.5) |

79.9 (26.6) |

66.8 (19.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

97.7 (36.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 45.2 (7.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

68.5 (20.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

87.7 (30.9) |

88.7 (31.5) |

86.3 (30.2) |

79.8 (26.6) |

67.7 (19.8) |

54.3 (12.4) |

44.5 (6.9) |

67.6 (19.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.4 (1.9) |

39.8 (4.3) |

47.4 (8.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

63.3 (17.4) |

72.9 (22.7) |

75.6 (24.2) |

73.6 (23.1) |

67.3 (19.6) |

55.6 (13.1) |

43.6 (6.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

55.3 (12.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.6 (−3.6) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

34.7 (1.5) |

40.2 (4.6) |

49.1 (9.5) |

58.2 (14.6) |

62.4 (16.9) |

60.9 (16.1) |

54.8 (12.7) |

43.4 (6.3) |

32.9 (0.5) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

43.0 (6.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 12.4 (−10.9) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

35.0 (1.7) |

47.5 (8.6) |

55.3 (12.9) |

54.1 (12.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

17.7 (−7.9) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

8.5 (−13.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 2 (−17) |

−12 (−24) |

10 (−12) |

20 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

48 (9) |

31 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

10 (−12) |

3 (−16) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.71 (18) |

0.85 (22) |

1.05 (27) |

0.88 (22) |

0.70 (18) |

0.61 (15) |

2.61 (66) |

2.66 (68) |

1.56 (40) |

1.33 (34) |

0.88 (22) |

1.08 (27) |

14.92 (379) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.0 (10) |

4.4 (11) |

3.7 (9.4) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

2.4 (6.1) |

6.9 (18) |

23.7 (60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 11.7 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 75.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 3.8 | 16.0 |

| Source: NOAA[55][59] | |||||||||||||

|

|

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org.

|

See or edit raw graph data.

Albuquerque is located near the crossroads of several ecoregions. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,[60] the city is located in the southeastern edge of the Arizona/New Mexico Plateau, with the Arizona/New Mexico Mountains ecoregion defining the adjacent Sandia-Manzano mountains, including the foothills in the eastern edges of the city limits, above Juan Tabo Boulevard. Though the city lies at the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert transitioning into the Colorado Plateau, much of Albuquerque area west of the Sandia Mountains shares similar aridity, temperatures, and natural vegetation more with that of the Chihuahuan Desert, namely the desert grassland and sand scrub plant communities.[61]

The eastern portion of the greater Albuquerque area are known as the East Mountain area, and they are within the Southwestern Tablelands, sometimes considered a southern extension of the central high plains and northeast New Mexico highlands. To the north is the Southern Rockies ecoregion in the Jemez Mountains.

The average annual precipitation is less than half of evaporation supporting an arid climate (BWk), and no month's daily temperature mean is below freezing. The climate is rather mild compared to parts of the country further north or further south. However, due to the city's high elevation, low temperatures in winter often dip below freezing. Varied terrain and elevations within the city and outlying areas cause daily temperature differentials to vary. The daily average temperatures in December and January, the coldest months, are above freezing at 36.9 °F (2.7 °C) and 37.4 °F (3.0 °C), respectively.

Albuquerque's climate is usually sunny and dry, with an average of 3,415 sunshine hours per year.[57][62] Brilliant sunshine defines the region, averaging 278 days a year; periods of variably mid and high-level cloudiness temper the sun, mostly during the cooler months. Extended cloudiness lasting longer than two or three days is rare.

Winter typically consists of cool days and cold nights, except following passage of the strongest cold fronts and arctic airmasses when daytime temperatures remain colder than average; overnight temperatures tend to fall below freezing between about 10 pm and 8 am in the city, except during colder airmasses, plus colder spots of the valley and most of the East Mountain areas. December, the coolest month, averages 36.9 °F (2.7 °C); the median or normal coolest temperature of the year is 12 °F (−11 °C), while the average or mean is about 11 °F (−12 °C). It is typical for daily low temperatures in much of late December, and January, and February to be below freezing, with a long-term average of 93 days per year falling to or below freezing, and two days failing to rise above freezing. In March, winds dominate as the temperatures began to warm late in the winter.[55]

Spring is windy, sometimes unsettled with rain, though spring is usually the driest part of the year in Albuquerque. Late March and April tend to experience many days with the wind blowing at 20 to 30 mph (32 to 48 km/h), and afternoon gusts can produce periods of blowing sand and dust.[citation needed] In May, the winds tend to subside as a summer-like airmass and temperatures begin to occur into with regularity. The warming and drying trend continues into June. By mid-June, temperatures can exceed 100 °F (38 °C).

Summer is lengthy and very warm to hot, relatively tolerable for most people because of low humidity and air movement. The exception is some days during the New Mexico monsoon, when daily humidity remains relatively high, especially in July and August. 2.6 days of 100 °F (38 °C) or warmer highs occur annually on average, mostly in June and July and rarely in August due in part to the monsoon; an average of 64 days experience 90 °F (32 °C) or warmer highs.[55] Despite the rarity of such heat, 28 days with highs at or above 100 °F (38 °C) occurred in the summer of 1980 at Albuquerque's Sunport. In September, the monsoon begins to weaken.[63] Portions of the valley and West Mesa locations experience more high temperatures above 90 °F (32 °C) and 100 °F (38 °C) as part of normal or extreme weather each summer.

Autumn is generally cool in the mornings and nights but sees less rain than summer, though the weather can be more unsettled closer to winter, as colder airmasses and weather patterns build in from the north and northwest with more frequency.[citation needed] Occasionally, snow will fall in late autumn in December; rarely in late November.

Precipitation averages 8.84 inches (225 mm) per year. On average, January is the driest month, while July and August are the wettest months, as a result of shower and thunderstorm activity produced by the monsoon prevalent over the Southwestern United States. Most rain occurs during the late summer monsoon season, typically starting in early June and ending in mid-September.[64]

Albuquerque averages 7.9 inches (20 cm) of snow per winter, and experiences several accumulating snow events each season. Locations in the Northeast Heights and Eastern Foothills tend to receive more snowfall due to each region's higher elevation and proximity to the mountains. The city was one of several in the region experiencing a severe winter storm on December 28–30, 2006, with locations in Albuquerque receiving between 10.5 and 26 inches (27 and 66 cm) of snow.[65] More recently, a major winter storm in late February 2015 dropped up to a foot (30 cm) of snow on most of the city. Such large snowfalls are rare occurrences during the period of record, and they greatly impact traffic movement and the workforce due to their rarity.[citation needed]

The mountains and highlands east of the city create a rain shadow effect, due to the drying of air descending the mountains; the Sandia Mountain foothills tend to lift any available moisture, enhancing precipitation to about 10–17 inches (254–432 mm) annually.[citation needed] Traveling west, north, and east of Albuquerque, one quickly rises in elevation and leaves the sheltering effect of the valley to enter a noticeably cooler and slightly wetter environment.[citation needed] One such area is considered part of Albuquerque Metropolitan Area, commonly called the East Mountain area; it is covered in woodlands of juniper and piñon trees, a common trait of southwestern uplands and the southernmost Rocky Mountains.

Albuquerque's drinking water comes from a combination of Rio Grande water (river water diverted from the Colorado River basin through the San Juan–Chama Project[66]) and a delicate aquifer that has been described as an "underground Lake Superior". The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority (ABCWUA) has developed a water resources management strategy that pursues conservation and the direct extraction of water from the Rio Grande for the development of a stable underground aquifer in the future.[67][68]

The aquifer of the Rio Puerco is too saline to be cost-effectively used for drinking. Much of the rainwater Albuquerque receives does not recharge its aquifer. It is diverted through a network of paved channels and arroyos, and empties into the Rio Grande.

Of the 62,780 acre-feet (77,440,000 m3) per year of the water in the upper Colorado River basin entitled to municipalities in New Mexico by the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, Albuquerque owns 48,200. The water is delivered to the Rio Grande by the San Juan–Chama Project. The project's construction was initiated by legislation signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, and was completed in 1971. This diversion project transports water under the continental divide from Navajo Lake to Lake Heron on the Rio Chama, a tributary of the Rio Grande. In the past much of this water was resold to downstream owners in Texas. These arrangements ended in 2008 with the completion of the ABCWUA's Drinking Water Supply Project.[69]

The ABCWUA's Drinking Water Supply Project uses a system of adjustable-height dams to skim water from the Rio Grande into sluices that lead to water treatment facilities for direct conversion to potable water. Some water is allowed to flow through central Albuquerque, mostly to protect the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow. Treated effluent water is recycled into the Rio Grande south of the city. The ABCWUA expects river water to comprise up to seventy percent of its water budget in 2060. Groundwater will constitute the remainder. One of the policies of the ABCWUA's strategy is the acquisition of additional river water.[68][70] : Policy G, 14

Residents of the city are known as Burqueños (masculine grammatical gender) or Burqueñas (feminine grammatical gender), or more rarely as simply "Albuquerqueans".[71] The Spanish terms are from Chicano slang (Caló).[72] "Burqueño" is also sometimes used as an adjective for anything related to that city,[73] or to specifically refer to someone who identifies with the Burqueños New Mexico prison gang, or one of the barrios within Albuquerque.[74][75] Burqueños often speak New Mexican Spanish and Western American English.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,315 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,785 | 63.5% | |

| 1900 | 6,238 | 64.8% | |

| 1910 | 11,020 | 76.7% | |

| 1920 | 15,157 | 37.5% | |

| 1930 | 26,570 | 75.3% | |

| 1940 | 35,449 | 33.4% | |

| 1950 | 96,815 | 173.1% | |

| 1960 | 201,189 | 107.8% | |

| 1970 | 244,501 | 21.5% | |

| 1980 | 332,920 | 36.2% | |

| 1990 | 384,736 | 15.6% | |

| 2000 | 448,607 | 16.6% | |

| 2010 | 545,852 | 21.7% | |

| 2020 | 564,559 | 3.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[76] 2010–2020[8][3] |

|||

| Historical racial profile | 2020[77] | 2010[78] | 1990[32] | 1970[32] | 1950[32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 49.2% | 46.7% | 34.5% | 33.1% | N/A |

| White | 70.3% | 69.7% | 78.2% | 95.7% | 98.0% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 38.3% | 42.1% | 58.3% | 63.3% | N/A |

| American Indian and Alaska Native persons | 4.5% | 4.6% | |||

| Black or African American | 3.1% | 3.3% | 3.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% |

| Asian | 3% | 2.6% | 1.7% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

According to the 2020 U.S. census, there were 564,559 people and 229,701 households in Albuquerque. The population density was 2,907.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,122.6/km2), making Albuquerque one of the least densely populated large cities in the U.S.

In 2020, the racial makeup of the city (including Latinos in the racial counts) was 60.3% White,[79] 4.5% Native American, 3.1% Black or African American, 3% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and 9.2% Multiracial (two or more races).[77] About half of all residents (47.7%) were Hispanic or Latino, of any race while non-Hispanic whites accounted for 37.7%.[80]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[81] | Pop 2010[82] | Pop 2020[80] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 223,895 | 229,933 | 212,966 | 49.91% | 42.12% | 37.72% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 12,376 | 14,878 | 16,649 | 2.76% | 2.73% | 2.95% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 14,813 | 20,627 | 25,195 | 3.30% | 3.78% | 4.46% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 9,689 | 13,674 | 18,041 | 2.16% | 2.51% | 3.20% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 339 | 418 | 483 | 0.08% | 0.08% | 0.09% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 682 | 1,224 | 2,888 | 0.15% | 0.22% | 0.51% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 7,738 | 10,043 | 19,099 | 1.72% | 1.84% | 3.38% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 179,075 | 255,055 | 269,238 | 39.92% | 46.73% | 47.69% |

| Total | 448,607 | 545,852 | 564,559 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

In 2010, about one-third of Albuquerque households (33.3%) had children under the age of 18, 43.6% were married couples living together, 12.9% had a female with no husband present, and 38.5% were non-families; 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.02.

In 2010, the age distribution was 24.5% under 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 30.9% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.0% who were 65 or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.8 males.

In 2010, the median income for a household in the city was $38,272, and the median income for a family was $46,979. Males had a median income of $34,208 versus $26,397 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,884. About 10.0% of families and 13.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.4% of those under age 18 and 8.5% of those age 65 or over.

The Albuquerque metropolitan area had 923,630 residents in July 2020.[4] The area includes Rio Rancho, Bernalillo, Placitas, Zia Pueblo, Los Lunas, Belen, South Valley, Bosque Farms, Jemez Pueblo, Cuba, and part of Laguna Pueblo. This metro is part of the larger Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Los Alamos combined statistical area (CSA), with a population of 1,171,991 as of 2016. The CSA constitutes the southernmost point of the Southern Rocky Mountain Front megalopolis, with a population of 5,467,633 according to the 2010 United States census, including other major Rocky Mountain region cities such as Cheyenne, Wyoming; Denver, Colorado; and Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Of the residents of Albuquerque who are religious, the majority of them are Christian.[84] Reflecting its long history as a Spanish city, Catholicism is the largest denomination; Catholics are served by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe, whose administrative center is located in Albuquerque.[85] Collectively, other Christian churches and organizations, such as the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy, among others, make up the second largest group. Baptists form the third largest Christian group, followed by Latter Day Saints, Pentecostals, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans and Episcopalians.

Judaism is the second-largest non-Christian religion in Albuquerque;[84] Congregation Albert, a Reform synagogue established in 1897, is the oldest extant Jewish organization in New Mexico.[25] Islam is the next largest minority religion, with an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 adherents, representing 85% of the state's Muslim population.[86] The Islamic Center of New Mexico is the largest mosque in Albuquerque, hosting daily prayers and activities for both Muslims and non-Muslims.[87]

The Albuquerque Sikh Gurudwara and Guru Nanak Gurdwara Albuquerque serve the city's Sikh population, while the main Hindu organizations are the Hindu Temple Society of New Mexico and Gayatri Temple.[88] There are several Buddhist temples and centers throughout the city, representing different movements and schools, such as Zen and Soka Gakki.[89]

Like many major American cities, Albuquerque struggles with homelessness, which has become more visible since the 2000s. According to Rock at Noon Day, a homeless services center, there were an estimated 4,000 to 4,500 homeless people living in the Albuquerque metropolitan area in 2019, with millennials and elderly accounting for the fastest growing segments.[90] Albuquerque Public Schools spokeswoman Monica Armenta said the number of homeless children enrolled in district schools (meaning children from families that have no permanent address) has consistently ranged from 3,200 to 3,500. The Coordinated Entry System, a centralized citywide system used to track and fill supportive housing openings when they become available, shows that about 5,000 households experienced homelessness in 2018.[90] Homelessness is particularly concentrated around Downtown, and also in the International District off Central Avenue, which suffers from chronic urban decay and drug use.[91]

Albuquerque hosts the International Balloon Fiesta, the world's largest gathering of hot-air balloons, taking place every October at Balloon Fiesta Park, with its 47-acre launch field.[92] Another large venue is Expo New Mexico, where other annual events are held, such as North America's largest pow wow at the Gathering of Nations, as well as the New Mexico State Fair. Other major venues throughout the metropolitan area include the National Hispanic Cultural Center, the University of New Mexico's Popejoy Hall, Santa Ana Star Center, and Isleta Amphitheater. Old Town Albuquerque's Plaza, Hotel, and San Felipe de Neri Church hosts traditional fiestas and events such as weddings, also near Old Town are the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Explora, American International Rattlesnake Museum, and Albuquerque Biological Park. Other notable museums in Albuquerque include the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History and the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta Museum and more can be found here. Located in Downtown Albuquerque are historic theaters such as the KiMo Theater, which is located across the street from the New Mexico Holocaust & Intolerance Museum, and the Albuquerque Little Theater. Near the Civic Plaza is the Al Hurricane Pavilion and Albuquerque Convention Center with its Kiva Auditorium. Due to its population size, the metropolitan area regularly receives most national and international music concerts, Broadway shows, and other large traveling events, as well as New Mexico music, and other local music performances.

Sandia Peak Ski Area, adjacent to Albuquerque, provides both winter and summer recreation in the Sandia Mountains. It features Sandia Peak Tramway, the world's second-longest passenger aerial tramway, and the longest in the Americas. It stretches from the northeast edge of the city to Sandia Peak, the summit of the ski resort, and has the world's third-longest single span. Elevation at the summit is roughly 10,300 ft (3,100 m) above sea level, or "ten-three".

Albuquerque is a hub for production studios, including Albuquerque Studios, which is one of the primary productions hubs for Netflix. Several major motion pictures and television shows have been filmed and produced in Albuquerque, including scenes from Walt Disney Presents Elfego Baca,[93][94][95][96] The Muppet Movie, the Breaking Bad franchise,[97][98][99][100][101] The Avengers,[102][103] A Million Ways to Die in the West,[104] In Plain Sight, Speechless, Daybreak, Just Getting Started, and Stranger Things season 4. NBCUniversal also has a sizable and expanding presence in the city, as do independent multimedia franchise studios.[105]

Numerous works of fiction take place, either fully or in part, in the Albuquerque metropolitan area. These include Albuquerque (a 1948 Western), Bless Me, Ultima, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Breaking Bad (along with its spin-offs Better Call Saul and El Camino), and High School Musical.[106] The city is referenced in Billy Mize's 1967 album Lights of Albuquerque, Jim Glaser's 1986 song "The Lights of Albuquerque", Neil Young's song "Albuquerque", and "Weird" Al Yankovic's song "Albuquerque". The city is referenced in "Hungry, Hungry Homer", the 15th episode of the twelfth season of The Simpsons, which features Albuquerque as the location where the owners of the Springfield Isotopes baseball team wish to relocate; the episode inspired the name of the real Albuquerque Isotopes Minor League team.[107] Many Bugs Bunny cartoon shorts feature Bugs traveling around the world by burrowing underground. Ending up in the wrong place, Bugs consults a map, complaining, "I knew I should have taken that left turn at Albuquerque." Failure to do so can somehow result in Bugs ending up thousands of miles off-course. (Bugs first uses that line in 1945's Herr Meets Hare.)[108]

The city is served by one major newspaper, the Albuquerque Journal, which, along with Albuquerque the Magazine, is distributed throughout the Southwestern United States and catalogued by the Library of Congress. The Journal is New Mexico's most widely circulated newspaper, and used to compete with The Albuquerque Tribune until 2008; today The Journal competes with The Santa Fe New Mexican and Las Cruces Sun-News. The Albuquerque metropolitan area itself has other local periodicals, Valencia County News-Bulletin, Rio Rancho Observer, Corrales Comment, and the student newspapers of The Lobo at University of New Mexico and CNM Chronicle at Central New Mexico Community College.

Albuquerque is also home to numerous radio and television stations that serve the metropolitan and outlying rural areas. Albuquerque is home to eighteen broadcast television stations, including KOB, KRQE, KOAT-TV, and KLUZ-TV, although most households are served by direct cable network connections. Comcast Cable nearly has a monopoly on terrestrial cable service in the city, but not throughout the entire Albuquerque-Santa Fe media market, which is ranked as the 48th largest television market in the United States, Comcast shares the metropolitan market with Cable One, Unite Private Networks, and various satellite and wireless providers.[109]

Christian media outlets in the city include Trinity Broadcasting Network which owns the KNAT-TV signal, and independent Christian broadcasting exists on KAZQ. Each of the Albuquerque metropolitan area's megachurches have media presence with broadcasts of their sermons, those include Legacy, Calvary, and Sagebrush. Christian radio is found on FM and AM through KLYT, KSVA, KDAZ, KFLQ, and KKIM.

One of the longest running AM broadcasts in the United States is an ABC News Radio station called KKOB (AM).[110] The first officially licensed FM radio broadcast in Albuquerque was KANW which mostly broadcasts the New Mexico music genre and NPR programming.[111][112]

Performers such as Al Hurricane, Al Hurricane Jr, Lorenzo Antonio, and Sparx popularized New Mexico's Hispano and Native American folk genre by blending it with rockabilly, jazz, Western, Norteño, Latin pop, and rock music.[113] Then mayor Richard J. Berry named the center stage of Albuquerque Plaza the "Al Hurricane Pavilion".[114][115] Regional folk and country music continues to be played on local radio, such as the New Mexico music genre–specific KANW, as well as KNMM on Saturdays, country radio stations KRST "92.1" and KBQI "The Big-I 107.9", along with KBQI's classic country "98.1 The Bull", and Regional Mexican radio on KLVO "Radio Lobo 97.7".

Other forms of American popular music are represented on FM radio: contemporary hit radio is featured on KOBQ. During the 1990s, the urban contemporary music radio format had two major stations, on "KISS 97.3" KKSS and "WILD 106" KDLW.[116] KISS 97.3 still exists today, though WILD has changed to a variety of formats. In the 2000s modern rock stations focusing on alternative rock, nu metal, and adult contemporary music became popular in the city, including the FM station KPEK "100.3 The Peak". During this time, contemporary Christian music garnered success with KLYT, branded as M88 in its earlier days, due to the crossover of Christian rock and Christian hip hop with popular music.[117][118]

Music groups based in Albuquerque include A Hawk and A Hacksaw, Beirut, The Echoing Green, The Eyeliners, Hazeldine, Leiahdorus, Oliver Riot, Scared of Chaka, and The Shins.

Talk radio has several outlets in the Albuquerque area. Including a public radio station run by The University of New Mexico KUNM-FM,[119] for conservative talk radio there is KIVA "The Rock of Talk" owned by Eddy Aragon,[120] and KKOB has a Cumulus Media station affiliated with ABC News Radio. As for sports radio there is KNML "The Sports Animal" and KQTM "The Team".

As a large and multicultural city, Albuquerque is home to a variety of global cuisines, in addition to local New Mexican cuisine. Many local restaurants receive statewide attention, with several becoming chains; the city hosts the headquarters of Blake's Lotaburger, Little Anita's, Twisters, Dion's, Boba Tea Company, and Sadie's, most of which offer New Mexican fare.

As the focus of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, the city is punctuated by agricultural acequias that contrast with the otherwise heavily urban settings. Crops such as New Mexico chile are grown along the entire Rio Grande; the red or green chile pepper is a staple of New Mexican cuisine and widely available in restaurants, including national fast-food chains. Likewise, the Albuquerque metro is a major contributor to the Middle Rio Grande Valley AVA, where New Mexico wine is produced at several vineyards; the river also provides trade access to the Mesilla Valley to the south (containing Las Cruces, New Mexico and El Paso, Texas), with its own wine offerings, and the adjacent Hatch Valley, which is well known for its New Mexico chile peppers. Albuquerque also has a burgeoning brewery scene.

The Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta takes place at Balloon Fiesta Park the first week of October. Although the global COVID-19 forced the cancellation of the 2020 event, The Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta successfully returned in 2021. It is one of Albuquerque's biggest attractions. Hundreds of hot-air balloons are seen every day, and there is live music, arts and crafts, and food.[121]

The original architecture of La Villa de Albuquerque is referred to as the Territorial Style, it was revitalized as the Territorial Revival architecture. Architect John Gaw Meem is often credited with this revival.[citation needed]

John Gaw Meem is also credited with developing and popularizing the Pueblo Revival style, which was based in Santa Fe but received an important Albuquerque commission in 1933 as the architect of the University of New Mexico. He retained this commission for the next quarter-century and developed the university's distinctive Southwest style.[24] : 317  Meem also designed the Cathedral Church of St. John in 1950.[122]

Pueblo Deco architecture was derived from Pueblo and Territorial styles meeting the Art Deco movement, and it is richly featured in downtown Albuquerque. Albuquerque boasts a unique nighttime cityscape, personified in the lights of Albuquerque, a common motif in art and song.[123][124][125] The city lights twinkle and glitter from views on Nine Mile Hill, it was among Elvis Presley's favorite views.[126] Route 66 era neon signs, and LED style versions of the neon-style are common throughout the city. Many building exteriors are illuminated in vibrant colors such as green and blue. The Wells Fargo Building is illuminated green.[citation needed] The DoubleTree Hotel changes colors nightly, and the Compass Bank building is illuminated blue. The rotunda of the county courthouse is illuminated yellow, while the tops of the Bank of Albuquerque and the Bank of the West are illuminated reddish-yellow. Due to the nature of the soil in the Rio Grande Valley, the skyline is lower than might be expected in a city of comparable size elsewhere, and it was used to highlight the low-lying architecture of heritage Pueblo and Hispano architectural styles.[citation needed]

Albuquerque has expanded greatly in area since the mid-1940s. During those years of expansion, the planning of the newer areas has considered that people drive rather than walk. The pre-1940s parts of Albuquerque are quite different in style and scale from the post-1940s areas. The older areas include the North Valley, the South Valley, various neighborhoods near downtown, and Corrales. The newer areas generally feature four- to six-lane roads in a 1 mile (1.61 km) grid. Each 1 square mile (2.59 km2) is divided into four 160-acre (0.65 km2) neighborhoods by smaller roads set 0.5 miles (0.8 km) between major roads. When driving along major roads in the newer sections of Albuquerque, one sees strip malls, signs, and cinderblock walls. The upside of this planning style is that neighborhoods are shielded from the worst of the noise and lights on the major roads.[citation needed]

The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Library system consists of nineteen libraries to serve the city, including the Main Library, Special Collections branch (Old Main Library), and Ernie Pyle branch, which is located in the former home of noted war correspondent Ernie Pyle.[127] The Old Main Library was the first library of Albuquerque and from 1901 until 1948 it was the only public library. The original library was donated to the state by Joshua and Sarah Raynolds. After suffering some fire damage in 1923 the city decided it was time to construct a building for the library to be moved to, however, by 1970 even after additions were made the population and library needs had outgrown the building for its use as a main library and it was turned into Special Collections. The Old Main Library was recognized as a landmark in September 1979. It was not until 1974 with the movement of the South Valley Library into a new building that the Bernalillo built and administered a public library. Not long after, in 1986, the Bernalillo and Albuquerque government decided that joint powers would work best to serve the needs of the community and created the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Library System.[128]

The Bosque is a major outdoors area in the city; it has numerous hiking and biking trails. The Sandia–Manzano Mountains and West Mesa also have many hiking trails, such as La Luz Trail and Petroglyph National Monument. According to the Trust for Public Land, Albuquerque has 291 public parks as of 2017, most of which are administered by the city Parks and Recreation Department. The total amount of parkland is 42.9 square miles (111 km2), or about 23% of the city's total area—one of the highest percentages among large cities in the U.S. About 82% of city residents live within walking distance of a park.

The Albuquerque Biological Park manages the ABQ BioPark Botanic Garden, ABQ BioPark Aquarium, Tingley Beach, and ABQ BioPark Zoo. Amusement parks in the city include Cliff's Amusement Park and Hinkle Family Fun Center;[129] there was formerly The Beach waterpark, which became a vacant lot on Desert Surf Circle for several years, until Topgolf made a driving range in the lot.[130]

There are numerous golf courses in the city area; Arroyo Del Oso Golf Course, Isleta Eagle Golf Course, Ladera Golf Course, Los Altos Golf Course, Paa-Ko Ridge Golf Club, Paradise Hills Golf Course, Puerto del Sol Golf Course, Sandia Golf Club, Santa Ana Golf Club, Twin Warriors Golf Club, and University of New Mexico's Championship Golf Course.

Albuquerque is home to over 300 other visual arts, music, dance, literary, film, ethnic, and craft organizations, museums, festivals and associations, and the state's capital Santa Fe is known for being a major arts city. One of the major art events in the state is the summertime New Mexico Arts and Crafts Fair, a nonprofit show exclusively for New Mexico artists and held annually in Albuquerque since 1961.[131][132]

The Albuquerque Isotopes are a minor league affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, having derived their name from The Simpsons season 12 episode "Hungry, Hungry Homer", which involves the Springfield Isotopes baseball team considering relocating to Albuquerque.[133]

On June 6, 2018, the USL Championship division announced its latest soccer expansion club with New Mexico United, who play their home matches at Rio Grande Credit Union Field at Isotopes Park.

Having been home to boxing mainstays Brenda Burnside, Bob Foster, and Johnny Tapia, Albuquerque later became home to Jackson Wink MMA gym.[134] Several MMA world champions and fighters, including Holly Holm and Jon Jones, train in that facility.[135][136] The PGA of America offers Albuquerque golf tournaments with Sun Country Golf House, including the Sun Country PGA Championship and the New Mexico Open which have been hosted in the metropolitan area several times.[137] Roller sports are finding a home in Albuquerque as they hosted USARS Championships in 2015,[138] and are home to Roller hockey,[139] and Roller Derby teams.[140]

While no longer operating in an official capacity, the defunct Albuquerque Dukes minor league baseball team still has a major following, and the Major League Baseball organization is aware of the team's continued popularity.[141] The Isotopes sometimes hold a Dukes Retro Night where they wear Dukes uniforms,[142] and The Duke mascot continues to be an icon of the city.[141][143]

| Team | Sport | League | Venue | capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albuquerque Isotopes | Baseball | Pacific Coast League | Rio Grande Credit Union Field at Isotopes Park | 13,279 |

| New Mexico United | Soccer | USL Championship | Rio Grande Credit Union Field at Isotopes Park | 13,279 |

| Albuquerque Sol | Soccer | USL League Two | Ben Rios Field | 1,500 |

| Duke City Gladiators | Indoor Football | Indoor Football League | Rio Rancho Events Center | 6,000 |

| New Mexico Lobos | NCAA Division I FBS Football | Mountain West Conference | University Stadium | 42,000 |

| New Mexico Lobos (men and women) | NCAA Division I Basketball | Mountain West Conference | The Pit | 15,411 |

| Duke City Roller Derby | Roller Derby | Wells Park Community Center | ||

| New Mexico Ice Wolves | Ice hockey | NAHL | Outpost Ice Arenas | |

| New Mexico Macanas | Ulama de Cadera | AJUPEME USA | Mesa Verde Community Center |

| Albuquerque registered voters as of July 2016[144] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 123,594 | 40.03% | |||

| Republican | 104,662 | 34.13% | |||

| Unaffiliated and third party | 78,404 | 25.57% | |||

Albuquerque is a charter city, exercising home rule as opposed to being directly governed by state law.[145][146] Its charter was adopted in 1917 and has been amended several times, most notably in 1974, when the municipal government was changed from a commission-manager system to its current mayor–council system. Under this arrangement, power is divided between a mayor who serves as chief executive,[145]: V  and a nine-member council that holds legislative authority.[145]: IV  The current mayor is Tim Keller, who was elected in 2017.

The mayor of Albuquerque holds a full-time paid position and is directly elected for four-year terms.[147] Members of the Albuquerque City Council serve part-time, paid positions and are elected from their nine respective districts for four-year terms, with four or five councilors elected every two years.[148] Elections for mayor and councilor are nonpartisan.[145]: IV.4 [146] Each December, a new council president and vice-president are chosen by and among council members.[147]

The city council has the power to adopt all ordinances, resolutions, or other legislation.[148] It meets twice a month in the Vincent E. Griego Council Chambers of the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Government Center.[149] Ordinances and resolutions passed by the council are presented to the mayor for his approval; if the mayor vetoes an item, the council can override the veto by a two-thirds vote of councilors.[145]: XI.3  Each year, the mayor submits a city budget proposal for the next year to the council by April 1, and the council acts on the proposal within the next 60 days.[145]: VII

Albuquerque's judicial system consists of the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court, which serves other municipalities and unincorporated areas in the county; the main Metropolitan Courthouse is located in downtown Judges serve in nineteen divisions and are subject to partisan elections by county voters every four years.

The Albuquerque Police Department (APD) is the chief law enforcement entity within city limits; the unincorporated area of Bernalillo County is policed primarily by the Bernalillo County Sheriff's Department. With approximately 1,000 sworn officers, APD is the largest municipal police department in New Mexico; in September 2008, it was the 49th largest police department in the country, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.[150]

Albuquerque serves as the county seat of Bernalillo County.[151] The City of Albuquerque and Bernalillo County share some social services, and have created a joint city-county commission called the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Government Commission (ABCGC).[152] In 1986, the City of Albuquerque and Bernalillo County governments entered the joint powers agreement that created the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Library System.[153] The Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center opened in 2003 and was jointly managed by the City of Albuquerque and Bernalillo County until 2006, and fully managed by Bernalillo County from 2006 to present.[154]

Albuquerque is New Mexico's leading economic center, accounting for half the state's economic activity.[155] The city's economy is highly diversified, centering on science, medicine, technology, commerce, education, media entertainment, and culture (particularly fine arts); construction, film production, and retail trade have seen the most robust growth since 2020.[156]

Albuquerque is the center of the New Mexico Technology Corridor, a concentration of institutions engaged in scientific research and development, which in turn forms part of the larger Rio Grande Technology Corridor that stretches from southern Colorado to southwestern Texas.[157] Major nodes within the corridor include federal installations such as Kirtland Air Force Base, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratories; private healthcare facilities such as Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute and Presbyterian Health Services; academic institutions such as the University of New Mexico and Central New Mexico Community College; and private companies such as Intel (which has a fabrication site in neighboring Rio Rancho), Facebook (with a data center in Los Lunas), Northrop Grumman, passive solar energy company Zomeworks, and Tempur-Pedic. The city was also the founding location of MITS and Microsoft.

Beginning with the Manhattan Project in the 1940s, federal labs such as Los Alamos, Sandia, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have cooperated on multidisciplinary research in the region; contractors for these facilities bring highly educated workers and researchers to an otherwise relatively isolated area, many of whom establish or work with local tech companies. The federal government spends roughly $4 billion annually in research and development in and around Albuquerque. Pursuant to the CHIPS and Science Act—federal legislation aimed at expanding domestic semiconductor manufacturing, research and development of new technology, and workforce training—the U.S. Department of Energy announced plans to construct a new 100,000-square-foot technology incubator for companies, academia, and national laboratories, as well as a new platform for facilitating the development of tech startups among minority communities.[158]

The governments of Albuquerque and New Mexico have sought to attract more private investment into technology startups.[159] The bioscience sector has experienced particularly robust growth, beginning with the 2013 opening of a BioScience Center in Uptown Albuquerque, which was the state's first private incubator for biotechnology startups; since then, New Mexico-based scientists have formed roughly 150 bioscience startups, many of which are based in the Albuquerque metropolitan area.[160] In 2017, the state-funded Bioscience Authority was established to help promote local industry development, particularly through public-private partnerships; the following year, pharmaceutical company Curia built two large facilities in Albuquerque, and in fall 2022 broke ground on a $100 million expansion of its local operations.[160]

Film studios have a major presence throughout New Mexico; Netflix maintains a major production hub at Albuquerque Studios. There are numerous shopping centers and malls within the city, including ABQ Uptown, Coronado, Cottonwood, Nob Hill, and Winrock. Outside city limits but surrounded by the city is a horse racing track and casino called The Downs Casino and Racetrack, and the pueblos surrounding the city feature resort casinos, including Sandia Resort, Santa Ana Star, Isleta Resort, and Laguna Pueblo's Route 66 Resort.

| 1 | Kirtland Air Force Base |

| 2 | University of New Mexico |

| 3 | Sandia National Laboratories |

| 4 | Albuquerque Public Schools |

| 5 | Presbyterian Healthcare Services |

| 6 | City of Albuquerque (Government) |

| 7 | Lovelace–Sandia Health System |

| 8 | Presbyterian Medical Services |

| 9 | Intel Corporation |

| 10 | State of New Mexico (Government) |

| 11 | Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. |

Albuquerque is home to the University of New Mexico, the largest university in the state and the flagship of the state public university system. Central New Mexico Community College is a county-funded junior college serving new high school graduates and adults returning to school.